Bilge Yabancı on youth groups cultivating Turkey’s religious nationalism

December 17, 2019

Turkey Book Talk episode #105 – Bilge Yabancı, Marie Curie Fellow at the University of Graz’s Centre of Southeast European Studies, on her paper “Work for the Nation, Obey the State, Praise the Ummah: Turkey’s Government-oriented Youth Organizations in Cultivating a New Nation”, published in the journal Ethnopolitics.

Based on original fieldwork conducted over almost two years, the article explores the often umbilical relationship between the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) and over a dozen youth organisations that share its goal of shepherding Turkey down a religious, nationalist, conservative course.

Download the episode or listen below.

Here’s a link to the paper itself.

Subscribe to Turkey Book Talk : iTunes / PodBean / Stitcher / Acast / RSS

Follow Turkey Book Talk on Facebook or Twitter

This is the last episode of 2019. The next episode will be published in THREE weeks, on the first Tuesday of 2020. Thank you for listening throughout this year!

Here’s the link to sign up to Raziye Akkoç and Diego Cupolo’s Turkey Recap weekly newsletter, mentioned at the end of the episode.

Become a member to support Turkey Book Talk and get loads of extras: A 35% discount on any of over 400 books in IB Tauris/Bloomsbury’s excellent Turkey/Ottoman history category, English and Turkish transcripts of every interview upon publication, transcripts of the entire archive of episodes, and an archive of 231 reviews written by myself covering Turkish and international fiction, history, journalism and politics. A great Christmas present!

Sign up as a member to support Turkey Book Talk via Patreon.

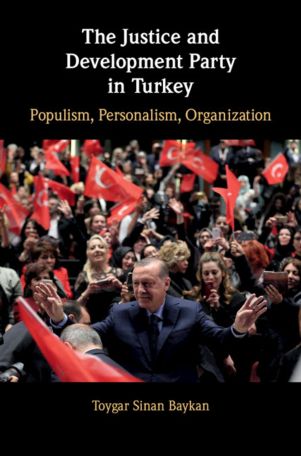

Turkey Book Talk episode #90 – Toygar Sinan Baykan, assistant professor at Kırklareli University, on “The Justice and Development Party in Turkey: Populism, Personalism, Organization” (Cambridge University Press).

The book is based on in-depth interviews with over 50 members at various levels of Turkey’s ruling party, giving an intimate glimpse of the AKP’s internal dynamics and how it benefits from various socio-cultural divides.

Download the episode or listen below.

Subscribe to Turkey Book Talk : iTunes / PodBean / Stitcher / Acast / RSS

Follow Turkey Book Talk on Facebook or Twitter

Join as a member to support Turkey Book Talk and get a load of extras: A 35% discount on any of over 400 books in IB Tauris/Bloomsbury’s excellent Turkey/Ottoman history category, English and Turkish transcripts of every interview upon publication, transcripts of the entire archive of 90+ episodes, and an archive of 231 reviews written by myself covering Turkish and international fiction, history, journalism and politics.

Sign up as a member to support Turkey Book Talk via Patreon.

Turkey Book Talk episode #43 – SONER ÇAĞAPTAY on his book “THE NEW SULTAN: ERDOĞAN AND THE CRISIS OF MODERN TURKEY” (IB Tauris).

Download the episode or listen below:

My review of this book is forthcoming in the Times Literary Supplement. Not sure of the publication date so keep your eyes peeled for that.

Subscribe to Turkey Book Talk : iTunes / PodBean / Stitcher / Acast / RSS

*SPECIAL OFFER*

You can support Turkey Book Talk by taking advantage of a 33% discount plus free delivery (cheaper than Amazon) on five different titles, courtesy of Hurst Publishers:

- ‘Jihad and Death: The Global Appeal of Islamic State’ by Olivier Roy

- ‘The Circassian: A Life of Eşref Bey, Late Ottoman Insurgent and Special Agent’ by Benjamin Fortna

- ‘The New Turkey and its Discontents’ by Simon Waldman and Emre Çalışkan

- ‘The Poisoned Well: Empire and its Legacy in the Middle East’ by Roger Hardy

- ‘Out of Nowhere: The Syrian Kurds in Peace and War’ by Michael Gunter

Follow this link to get that discount from Hurst Publishers.

Another way to support the podcast, if you enjoy or benefit from it: Make a donation to Turkey Book Talk via Patreon. Many thanks to current supporters Michelle Zimmer, Steve Bryant, Jan-Markus Vömel, Celia Jocelyn Kerslake, Aaron Ataman and Andrew MacDowall.

Michael Wuthrich on the history of elections in Turkey and the future of Turkish democracy

September 17, 2016

New Turkey Book Talk episode with Michael Wuthrich, chatting about “National Elections in Turkey: People, Politics and the Party System” (Syracuse University Press).

This really is an excellent book that overhauls much conventional wisdom about Turkish politics shared by right and left.

Unlike the deceptively boring title of the book, this episode’s title is stupidly ambitious. But we do cover a lot of ground. I’m really pleased with it – hope you enjoy/learn from it.

Download the episode or listen below.

Subscribe to Turkey Book Talk : iTunes / PodBean / Stitcher / Facebook / RSS

Here’s my review of the book in HDN.

Many thanks to current supporters Özlem Beyarslan, Steve Bryant, Andrew Cruickshank and Aaron Ataman.

The rise of political Islam in Turkey

March 7, 2015

My review/interview double-header this week was based on “The Rise of Political Islam in Turkey: Urban Poverty, Grassroots Activism and Islamic Fundamentalism” by Kayhan Delibaş, who works at Kent University and Turkey’s Adnan Menderes University.

The book is well worth reading for anyone looking for a deeper look into the political context of the emergence of Islamist parties in Turkey in the 1980s and 1990s. While it’s true that political Islam is an intrinsically transnational phenomenon, it’s always worth remembering the specific conditions that have facilitated it’s emergence, which of course differ everywhere.

Here’s my review of the book in the Hurriyet Daily News.

And here’s my conversation with its author Kayhan Delibaş.

Karşı and Turkey’s ‘opposition problem’

March 12, 2014

Swimming against all economic logic, another new national newspaper appeared on Turkey’s newsstands last month. Karşı means “against” or “anti” in Turkish, and this new daily has a slogan declaring it “Against lies, the newspaper of the truth,” apparently channelling the spirit of Çarşı, (the Beşiktaş football club supporters group whose motto is “against everything”). Karşı has quite a varied team of people working on it, but in many ways it embodies Turkey’s chronic “opposition problem.” The fragmented opponents of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) comprise leftists, liberals, Kemalists, nationalists, communists, environmentalists, anti-capitalist Muslims, and now Gülenists. But together these forces not only fail to make up a majority of the Turkish electorate, they are also handicapped by their diversity; the opposition is so disparate that it can agree on little other than that the AKP is a disaster.

The anti-government Gezi Park protests that raged throughout last summer made this point particularly clearly. The protests were full of energy and ideas, but it was the kind of energy that can’t be channelled through traditional political channels. The variety that made the Gezi movement so strong and impressive is exactly what prevents it from being an effective opposition force in more formal terms. What’s more, all Turkish opposition has to contend with a highly cohesive and disciplined incumbent government, confident in the loyalty of its core conservative constituency and backed by a well-oiled media and electoral machine.

Karşı’s first front page on Feb. 9. The headline reports PM Erdoğan’s order to hapless Habertürk controller Fatih Saraç, demanding that he cut a live broadcast in which Islamic theologian Yaşar Nuri Öztürk criticised the government.

In a recent Reuters piece about the durability of the AKP’s appeal, Hakan Altinay of the Brookings Institution is quoted as saying that there is “no political force to pick up the ingredients and cook a better meal, the opposition has no sense of direction.” Indeed, it is commonly assumed that the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) is too clumsy and loaded with its own historical baggage to be effective. There’s some truth in this, but it’s hard to see how anyone could channel the disaffection of Turkey’s hugely varied opposition into a single coherent political party, while at the same time outlining a vision that can defeat the AKP at the ballot box. Similarly, Piotr Zalewski wrote last week that the CHP would “have to deliver more than just finger pointing for Turkish voters to entrust it with running the country.” That’s also true, but the party is paralysed by the fact that finger pointing is pretty much the only thing that unites those ranged against the government. A more constructive platform might target wavering AKP voters (however few they are), but that would likely risk losing the CHP’s own wavering voters. It’s an almost impossible balancing act. Of course, none of this is particularly new, but it has become particularly obvious in the lead up to the March 30 local elections.

The new newspaper Karşı – with its diverse but incoherent range of ideas about what is to be done – perhaps embodies the Gezi conundrum. As its editor-in-chief Eren Erdem has said: “The Gezi spirit excites us, and we are talking the same language as the people on the streets during the Gezi resistance. From our writers to our editors, from our printers to our correspondents, we all imagine a free world.” Of course, Karşı is a newspaper, not a political party, but its example does indicate the challenge facing any formal opposition hoping to capitalize on the AKP’s current problems.

Rift with Gülen movement exposes rise of ‘Erdoğanist’ media

December 16, 2013

The spat between Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the movement of Islamic preacher Fethullah Gülen has seen tension between erstwhile allies in the Turkish media boil over into open hostility. Among many other things, the public drawing of swords – ostensibly over the closure of private examination schools (dershanes) – has exposed the extent to which PM Erdoğan has successfully built himself a support network of personally loyal media outlets. This network was already clear to see, but its guns have never before been so openly turned on the Gülenists.

Of particular note is the staunchly pro-Erdoğan line taken these days by daily Akşam, which was among the assets seized from Çukurova Holding by the state-run Savings Deposit and Insurance Fund (TMSF) over debt issues in May. After the seizing of Akşam, former editor-in-chief İsmail Küçükkaya was fired and the TMSF appointed a former Justice and Development Party (AKP) deputy in his place, while major changes were also made to the paper’s wider editorial team. Its previously centrist tone changed immediately, and Akşam became one of the most reliable supporters of the government throughout the summer’s Gezi Park protests. After the prep school polemic exploded, Akşam again rallied behind Erdoğan, taking its place alongside Sabah, Star, Türkiye, Yeni Şafak, Yeni Akit, Takvim, and Habertürk, in the ranks of pro-government newspapers launching unprecedented attacks on the Gülen movement. As with the others, this is clear simply from the number of front page headlines repeating whatever belligerent words the prime minister said on the subject on the previous day.

Although the new editorial board shifted Akşam’s position months ago, it was actually only sold to businessman Ethem Sancak last month, (along with TV station SkyTürk360, also seized from Çukurova Holding). Sancak once described himself as being “lovesick for the prime minister,” and openly declared that he had “entered the media sector to support Erdoğan.” He previously bought daily Star and news station Kanal TV back in 2006, transforming them into firmly pro-AKP voices before selling them on soon afterwards. Both processes resemble the way that Sabah, one of Turkey’s top-selling newspapers, was sold to the prime minister’s son-in-law in 2007, since when it has taken perhaps the most unswervingly pro-Erdoğan line of all mainstream newspapers. Through such moves, Erdoğan has gradually built up a media base completely loyal to himself, without which he would never have been able to achieve a position of such authority in the country. It has been a conscious effort; the bitter power struggles that have marked Erdoğan’s political career have convinced him of the need for a reliant and disciplined media support network, and the intertwining interests of business and political elites in Turkey allowed this network to be cultivated. This new, rigidly “Erdoğan-ist” media base has been more apparent than ever during the row with the Gülen movement.

The AKP government has sought to take the sting out of the dershane issue, announcing that the “transformation” of prep schools into private schools doesn’t have to be completed until September 2015 (conveniently after the three upcoming elections). The electoral effects of the Erdoğan-Gülen rift are still being speculated on, but it’s clear that although a detente has been declared for now, the knives will be even sharper when they inevitably come out again.

‘Gezi Park protests fuelled by foreign media’

June 13, 2013

One of the saddest aspects of the Turkish government’s response to the Gezi Park protests has been its line that the demonstrations are all a part of a “foreign plot” to bring down Turkey. As with everything else, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan fired the starting pistol, singling out the phantom international “interest rate lobby” as being behind the unrest. Since then, leading government figures have been falling over themselves to slander the protests as part of a “foreign conspiracy” by forces “jealous of Turkey’s economic success.” Economy Minister Zafer Çağlayan said “foreign circles” were trying to “undermine the country’s progress” through the protests: “This is totally an attempt to create a foreign hegemony on Turkey, but we are no fools.” EU Minister Egemen Bağış stated: “It is interesting to have such incidents in Turkey when … economic and development figures are at their best levels. The interest rate lobby and several financial institutions are disturbed by the growth and development of Turkey.” Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu said a deliberate propaganda operation was being conducted by the international media to tarnish Turkey’s image. Delusional? Yes. Seductive for a sizable portion of the Turkish electorate? Undoubtedly.

Overturning every stone only to find a nefarious foreign plot hidden underneath is one of Turkey’s less attractive national pastimes. Considering the past 200 years of the country’s history, it’s understandable, if not excusable. The current government was supposed to have broken with this paradigm. It had opened the country out to its region – both Europe and the Middle East – and was open-minded about doing business abroad and attracting investment for domestic infrastructure projects. The old embattled Turkish borders seemed to be opening to the world. However, the government’s reaction to the Gezi protests has laid bare all its latent insecurity and resentment, which has been most clear in the verbal attacks on the international coverage of the events. While mainstream domestic media has been brought (almost) completely under the thumb of the authorities, one gets the impression that the AKP’s open anger at the international media is now a kind of reflex action, indicating its frustrated inability to control what is being reported. The BBC must have been exaggerating the scale of the protests, as it wasn’t showing a penguin documentary.

Pro-government news outlets have been keen to assist in framing this paranoid narrative. While it was certainly no secret before, the Gezi protests have exposed the full extent of AKP control over the state news agency, Anadolu Ajansı, which has carried some utterly ridiculous The Onion-like headlines about foreign plots and jealous foreign powers. Pro-government newspapers have also loyally joined in, here’s daily Sabah applauding the aforementioned Anatolia for “sending a missile” to Reuters and CNN, by tweeting that 3G services had been cut in London, preventing them from broadcasting coverage of the police operation on the anti-G8 protests. Which to believe: Reuters or Anadolu Ajansı?

I also feel that this embattled sense is probably compounded by the shock of having international media ask genuinely tough questions of Turkish government representatives. Not only does this surprise AKP figures conditioned to having it easy with domestic journalists, but it also reinforces the sense among many government supporters that the international media is now “out to get” it (and, by extension, bring Turkey down). CNN International’s Christiane Amanpour was criticised by many pro-government Turks, (and praised by many protesters), simply for asking (not unusually) tough questions of Erdoğan’s advisor İbrahim Kalın. In fact, she did nothing out of the ordinary, but it must have been striking for anyone accustomed to toothless “interviews” such as the one conducted by Fatih Altaylı with Erdoğan on June 2.

Still, although they may make no logical sense, countering conspiracy theories with rational facts is a fool’s errand. David Aaronovitch wrote in a recent book on the subject that conspiracists tend to be on the “losing side” and conspiracy theories are mostly an expression of their insecurity; it’s therefore both strange and sad that rumours of “foreign plots” behind Turkey’s protests are being spread by a government that won 50% in the last election.

Coverage of Ankara-PKK ‘peace process’ in the Turkish media

January 19, 2013

Peace talks are still ongoing between the Turkish state, representatives of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), and PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan. It is likely that for any kind of peace to be secured they will have to go on for quite a while longer. Looking at the attitudes adopted by the Turkish media over the course of the “İmralı process” has been illuminating, particularly the reporting of the Jan. 17 funeral ceremonies in Diyarbakır of the three female Kurdish activists who were recently shot dead in Paris.

The government’s previous “Kurdish Opening” in 2009 came to an abrupt end after the controversy that followed the release of a group of PKK militants at the Habur border crossing and their welcoming back by huge crowds in Diyarbakır. Any comparable scenes carried the danger of enflaming Turkish nationalist sentiments and posed a risk to the latest dialogue process. Thus, in the lead up to the funerals most in the mainstream media were in agreement that they represented a significant test. On the morning of the ceremonies, dailies Vatan, Yeni Şafak, and Yeni Asya all featured front page headlines quoting the words of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan saying that the day would be a “Samimiyet sınavı,” or “Sincerity test.”

The ongoing process is extremely delicate. It’s easy to forget that although public support for the current PKK talks is significantly higher than it was in 2009, suspicion of the talks is still widespread. It was therefore interesting to observe how none of the major TV stations covered the ceremonies live in any detail on the day, despite the fact that they were attended by tens of thousands of people. As with much coverage of the Kurdish issue, (the Uludere/Roboski massacre in December 2011, for example), it is likely that this low key coverage had been “suggested” to the major media organizations by the government, acutely aware of the need to avoid scenes similar to those in Habur in 2009. Tellingly, Deputy Prime Minister Bülent Arınç had the following to say at a media event on Thursday: “The media’s support is so pleasing for us. I know and I see this support. … Eighty percent of media groups are lending their support. They are conducting positive broadcasts and contributing to the process. I hope this continues.” Still, in a column the next day titled “Peace is difficult with this media,” daily Vatan’s Rüşen Çakır had some critical things to say about this mentality:

“Television stations who didn’t show the ceremony yesterday failed the ‘sincerity test.’ In fact, they didn’t even sit the test … In the name of not making mistakes, or avoiding possible crises, or not annoying the government, they chose not to do anything at all … During the latest İmralı process, our media sees only one side as having to take steps – and all of these steps set according to what the government wishes – which itself sabotages the road to peace.”

In the event, Jan. 18’s newspapers exhaled an audible sigh of relief that the day passed without “provocation or sabotage” from either the mourners or the Turkish security forces. In contrast to the relative silence of the TV stations, the majority of the next day’s papers featured the funerals as front page headline stories, showing pictures of the crowds gathered in Diyarbakır and striking a noticeably optimistic tone. Many focused on a makeshift sign that one man was carrying at the ceremonies: “There is no winner from war; there is no loser from peace.”

That the funerals passed peacefully was a relief not only for the government but also for the Peace and Democracy Party (BDP), which shares grassroots with the PKK. At the moment, both the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government and the BDP have a common interest in continuing the talks. For the process to come to a successful conclusion – still a long way off – this shared interest will need to persist for a while yet.

On Friday Dec. 14, news of resignations from daily Taraf filtered out, with editor-in-chief Ahmet Altan, assistant editor Yasemin Çongar, and columnists Murat Belge and Neşe Tüzel resigning from their posts at the paper.

Founded in 2007, Taraf has become one of the most controversial and agenda-setting newspapers over the last five years. Originally set up by a group of like-minded liberals and leftists, the paper became renowned for its anti-military stance, publishing a series of highly-controversial stories that revealed the extent of the Turkish military’s involvement in daily political affairs. Taking on the once-mighty Turkish military saw Taraf regularly prefixed with adjectives like “plucky” and “brave,” and even lead to its accreditation from military press releases being cancelled. However, as question marks have steadily increased over the inconsistencies and judicial irregularities of anti-military crusades such as the Ergenekon and Balyoz cases, differences of opinion within Taraf have become increasingly evident. Altan’s editorials became increasingly critical of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government, creating friction within the paper that I previously wrote about here and here. This divergence of opinion appears to be the main reason behind the latest resignations, with the more critical, anti-AKP voices having been purged, (it is strongly rumoured that they have gone – like many in other newspapers – following government pressure).

Taraf’s front page banner on Dec. 15, showing Altan and Çongar. The headline reads: “We are grateful”

Most have assumed that the resignations bring about the effective the end of the paper. Nevertheless, Taraf patron Başar Arslan apparently intends to continue publication, announcing to the Istanbul Stock Exchange on Monday that former managing editor Markar Esayan had “temporarily” taken over its editorial chair. Nevertheless, a number of important names from Taraf’s Ankara bureau signed an open letter addressed to Arslan, stating:

“If Ahmet Altan and Yasemin Çongar go, it means that we go too … We are sure that Altan’s removal from the newspaper was a political decision … Our last word is this: We are waiting for Altan and Çongar to be returned to their previous positions as soon as possible.”

Following the resignations, veteran Turkish media observer Yavuz Baydar described the events at Taraf as “a new wound for journalism.” In a similar tone, Taraf columnist Emre Uslu wrote in Today’s Zaman:

“This crisis is a benchmark by which to understand the standards of Turkish democracy because Taraf was the last bastion of refuge for democrats and civilian opposition, who fought alongside the AK Party government against the military but turned against this government as it moves away from democratic standards … Taraf was criticizing the government for not bringing about and not institutionalizing democratic standards, yet ironically the paper became the victim of the system it has been criticizing for a long time.”

Milliyet columnist Kadri Gürsel wrote what was effectively an obituary for Taraf, describing it as a “zombie paper” that had now outlived its original purpose:

“With the ‘spirit of Taraf’ Ahmet Altan having left, the paper will from now on be a zombie … Taraf was established as a newspaper with a mission … Its aim was to purge the military from politics, ‘demilitarisation.’ But it has become clear that democratisation does not necessarily follow demilitarisation and civilianisation.”

Meanwhile, Dani Rodrik, (who moonlights as the leading name writing in English on the contradictions and irregularities of the Ergenekon and Balyoz cases – found on his blog here), conspicuously used the past tense to describe Taraf on Twitter:

“Taraf’s journalistic standards were absolutely the pits. Calling the publication ‘liberal’ is a great insult to liberals … Taraf published countless bogus ‘exposes’ fed to it by the police. Its motto was ‘we will publish any trash as long as its anti-military’ … In the name of democracy, Taraf voluntarily cooperated with a gang and together violated the rules of media ethics.”

Still, correct as Rodrik is, that doesn’t necessarily mean that the recent resignations don’t also represent “prime evidence of how much Turkey is slipping backwards,” as written by Yigil Schleifer – both can be true. If the past tense can really now be used to discuss Taraf, perhaps it can also finally be used to talk about any remnants of liberal Turkish sympathy for the AKP. With the passing of Taraf perhaps a chapter in Turkish politics also passes, and the last (much belated) nail can finally be hammered into the coffin of the 10-year-long flirtation between liberals and the AKP.

‘Bring back capital punishment, end this business’

November 14, 2012

Recently, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has repeatedly expressed his opinion that Turkey should consider reinstating capital punishment “in certain situations.” He first brought the issue up at a meeting of his Justice and Development Party’s (AKP) deputies on Nov. 3, in reference to Abdullah Öcalan, the convicted leader of the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), and has returned to it on a number of occasions since. “Right now a lot of people in public surveys say that capital punishment should be reintroduced … It is legitimate in certain situations,” Erdoğan said. “Yes, the death penalty was removed from Europe, but has it left America, Japan and China? Then there is a justified cause for the death penalty to remain.”

Capital punishment was abolished by Turkey in 2002, just prior to the AKP’s accession to power in the general elections of that year. Although no execution had been carried out by the Turkish state since 1984, an official end to the practice on the Turkish law books was seen as one of the key steps in Turkey’s EU accession process, which was then entering its most energetic period. The decision was fairly controversial at the time, as PKK leader Öcalan was captured and sentenced to death by the Turkish authorities in 1999. With the abolition of capital punishment, this sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, and Öcalan has since been held in a remote prison on İmralı Island in the Marmara Sea. With the recent spike in clashes between the Turkish security forces and the PKK, Erdoğan’s words on capital punishment should be interpreted in terms of the government’s failure to solve the Kurdish question – populist sentiments aiming to deflect nationalist criticism that he has made too many concessions to Kurdish rights with little to show in return.

The most striking newspaper coverage of the issue I saw came from popular pro-government daily Sabah, the newspaper with the fourth highest circulation nationally. Its Nov. 13 front page carried the bold headline “Bring back capital punishment, end this business.” These were the words of Fatma Çınar, the mother of one of the 17 soldiers killed in the recent helicopter crash in the southeastern province of Siirt, speaking at her son’s funeral. The crash was not a result of direct clashes with the PKK, but it was enough for PM Erdoğan to frame it as taking place within “much intensified, multi-dimensional” military operations in the region.

The return of the issue to the national debate has predictably raised eyebrows among those parts of the media who retain forlorn hopes that Turkey’s EU accession process can still be revived from its current moribund state. Opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) deputy Rıza Türmen, who worked for 10 years at the European Court of Human Rights, wrote in Milliyet on Nov. 13: “Capital punishment is banned according to the third section of the European Union’s founding principles, and the lifting of capital punishment is a precondition for membership of the EU and the European Council … Is leaving the EU process what the prime minister actually wants?” Meanwhile, Taraf editor Ahmet Altan’s disillusionment continued on the same day: “We’ve gone from a country that celebrated with enthusiasm the opening of ‘full EU membership negotiations,’ to one with a prime minister – like a funeral undertaker – shouting ‘hang them, hang them’ at every opportunity.” A response even came from the murky corridors of the EU itself, with Peter Stano, the spokesman for Enlargement Commissioner Stefan Füle, stating: “Our position on this is quite clear. Countries wishing to be a member of the EU cannot practice capital punishment. If capital punishment comes, the EU goes.”

Meanwhile, the hunger strikes of 700 Kurdish prisoners today entered their 64th day. Despite the increasing urgency of the situation, Erdoğan has so far ignored calls to directly engage in finding a solution. He even spent Nov. 12 in his hometown of Rize, receiving an honorary doctorate from the newly-established “Recep Tayyip Erdoğan University” (it’s sometimes difficult to tell in Turkey that you’re not reading The Onion). His words on capital punishment have certainly been an effective tactic distracting some attention away from the critical situation of the strikers. However, like the Peace and Democracy Party’s (BDP) recent remarks about erecting a statue of Öcalan, they have hardly done much to help create an atmosphere congenial to a solution.